Devblog #1 - Housekeeping

Welcome to the very first devblog 🎉

If you don't know what this project is about, let me briefly introduce it:

With that in mind, the content of todays devblog consists mostly of housekeeping, more specifically better naming for types and removing accumulated cruft.

Housekeeping surrounding the Provider

Better naming

The purpose of the Provider is to return the package.json for a given module.

Since the beginning it had this interface:

export interface IPackageVersionProvider extends Partial<INpmPackageProvider> {

size: number;

getPackageByVersion: (...args: PackageVersion) => Promise<INpmPackageVersion>;

getPackagesByVersion: (modules: PackageVersion[]) => AsyncIterableIterator<INpmPackageVersion>;

}

Given the explanation just before it's not immediately clear from the interface what its purpose is, worse there's also some cruft in there like extends Partial<INpmPackageProvider> and size: number.

If we just look at the core functionality we get this:

export interface IPackageVersionProvider {

getPackageByVersion: (...args: PackageVersion) => Promise<INpmPackageVersion>;

getPackagesByVersion: (modules: PackageVersion[]) => AsyncIterableIterator<INpmPackageVersion>;

}

Even though I'm accustomed to the code sometimes I have to pause and think which of those 2 interfaces gets me the package.json: IPackageVersionProvider or INpmPackageProvider. It's IPackageVersionProvider.

Also what's INpmPackageVersion? It's simply the package.json data.

To remove this ambiguity I opted to incorporate package.json more directly in the interface:

export interface IPackageJsonProvider {

getPackageJson: (...args: PackageVersion) => Promise<IPackageJson>;

getPackageJsons: (modules: PackageVersion[]) => AsyncIterableIterator<IPackageJson>;

}

Now I think its intent and purpose is much better communicated. Not that happy with getPackageJsons as I don't think it rolls easily of the tongue but it will have to do for now.

Removal of INpmPackageProvider from the Provider

The purpose of the INpmPackageProvider interface was to get package metadata for a given package provided by NPM. It basically contains all the package.json for all versions plus the dates when it was released and other metadata. It looked like this:

export interface INpmPackageProvider {

getPackageInfo(name: string): Promise<INpmPackage | IUnpublishedNpmPackage | undefined>;

}

The idea was to check for the implementation of this interface on the Provider and do some extra stuff, like displaying the release date. As said, the Provider returns a package.json this might come from an online source or from the local filesystem. But the data from INpmPackageProvider needs to be fetched online, this data will not become available via npm install on the filesystem. So it feels weird to attach INpmPackageProvider (which is online dependant) to the Provider interface which can work entirely offline.

Again, this was there since the very beginning but over time new API's emerged that made this specific case doable in a generic way namely via Decorators. Decorators are a way to attach additional data, which this NPM metadata file definitely is. Infact there's already a ReleaseDecorator which utilizes the INpmPackageProvider interface.

So I just deleted it from the now renamed IPackageVersionProvider and.... nothing happened. The code didn't rely on this interface being part of the Provider 🙌

Lastly to better convey its intent, it was also renamed to IPackageMetaDataProvider:

export interface IPackageMetaDataProvider {

getPackageMetadata(

name: string

): Promise<IPackageMetadata | IUnpublishedPackageMetadata | undefined>;

}

Removal of the size attribute

As said the job of the Provider is to return the corresponding package.json for a given package.

Where it gets that data, offline or online, is subject to the implementation of the Provider.

The size attribute would return the count of package.jsons it could return.

But what do you return if you fetch it from online sources? Or more specifically, what's the purpose of having the size attribute? What can you do with it?

Short: Nothing. Or in this case, to use it in unit tests. Its actual and only usage was to verify that the implementation of the FilesystemProvider found all package.json on the filesystem during test execution. In case of the OnlineProvider it just returned the number of already downloaded package.json. How useful.

I like unit tests, I prefer to be safe than sorry but the size attribute is part of a public interface and ultimatively it's not useful. It's just a burden for anyone trying to get into the code.

Also I didn't want to make it private and then convince TypeScript in the unit tests that I know what I'm doing by accessing this private attribute publicly etc. It had to go, so ultimatively I deleted the whole thing.

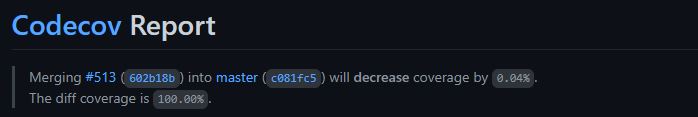

Code coverage dropped by 0.04%:

Which is unfortuante but given it's only 0.04% while in turn leaving the code base in a leaner state, I think it's the right tradeoff.

Removal of the start argument

Since the dawn of time start of the project, the visit method looked liked this:

visit: (callback: (dependency: T) => void, includeSelf: boolean, start: T) => void;

The visit method is used to traverse the dependency tree, it is part of the Package class and the start argument was meant as a way to only traverse a subtree, like this:

const root: Package;

const someDependency: Package;

//only visit a subtree, everything under someDependency

//true includes someDependency itself

root.visit(dependency => {}, true, someDependency);

But since the Package class is nested in nature and since you need a reference to your start Package anyway, you could just directly do:

someDependency.visit(dependency => {}, true);

Making the start argument useless.

It was a nice idea in the beginning but ultimatively it turned out to be not needed. Worse, when I removed the argument from the interface, I expected some refactoring but TypeScript didn't complain, it wasn't used anywhere! While I try not to fall victim to YAGNI (You Aren't Gonna Need It), I failed in this case as the only reason why it ended up in the code was because I thought I would need it, turns out I didn't.

Index signature for IPackageJson

This was just a small convenience update. The IPackageJson interface resembles the data in a package.json.

export interface IPackageJson {

name: string;

version: string;

description: string;

//....

}

But it was hardcoded to the values provided by the interface which is very inflexible.

Also it's impossible to statically type a dynamic data structure like package.json where you can add anything you want really.

It might work in simple cases like this:

const react: IPackageJson = await provider.getPackageJson("react");

console.log(react.description);

but if you're trying to query something that is not defined in the interface, you'll get hit with the following error:

const react: IPackageJson = await provider.getPackageJson("react");

//Property 'browserlist' does not exist on type 'IPackageJson'.

console.log(react.browserlist);

That's rather inflexible especially as there's no standard for a package.json and people are used to extend it however they want anyway.

So to make it possible to lookup custom keys I added an Index Signature to the interface:

export interface IPackageJson {

name: string;

version: string;

description: string;

//....

[key: string]: unknown;

}

If the key doesn't exist on the interface it will get the unknown type rather than generating an error.

While the IPackageJson interface already defines some attributes and its types it's actually not guaranteed that this will be the case at runtime... it might actually be better (more typesafe) to also assign them unknown just to be on the safe side, but it worked so far. If this changes in the future it will definitely be material for a new #devblog.

That said, that's all for this very first #devblog.

If you liked what you read you might want to follow me on Twitter to get notified about new #devblogs.

Or if you want to contribute to the project you can find the GitHub project here.